Having trouble with the letter “I”?

Much is written about the silencing of women, without understanding the ways in which we silence ourselves.

If someone asks you directly what you want from life, can you answer? Equally difficult might be the question, why do you want to be a writer? Sometimes, these answers lie so deep in our inner being, that reaching the reasons why requires gaining access to the “I” self we simply don’t talk to often enough, largely because we’ve been conditioned not to.

The problem with being conditioned not to ask ourselves direct questions (“Is this what I want?” “Am I happy?” “What is it I need from life?”) is that we become voiceless; we silence ourselves, and so we become complicit in our inability to be heard by a society that isn’t necessarily encouraging us to have specific needs focused on what’s going on in your inner landscape.

You might even feel lost in your inner landscape; I know I’ve been without a map often enough. Whereas you might know precisely what your kids or significant other wants, you might not be able to put your finger on your own wants and needs.

Even in this day and age, even in a society that promotes women’s issues, it’s rare to be asked a direct question about who you are, what you want, and what you need. If I ask you to tell me about yourself, your life, and why you want to write, what will you answer? You might be stymied. It might be the first time in your life someone has asked you directly to account for what’s going on inside of you—and that’s understandable, but it’s not acceptable for our society to ignore this about ourselves, and I’ll tell you why.

The reasons you or I might have some trouble with the use of the personal pronoun, making it so we are effectively silenced when someone asks us about ourselves, are complicated—much more complicated than the feminist movement has ever been able to get at the root of, in my experience.

The reasons we all have trouble from time to time with the personal pronoun has to do with how we’ve been socialized. This is less a gendered issue than it is a societal one—meaning that everyone, female and male, is affected by this problem, to a greater or lesser extent.

I noticed quite awhile ago that in spite of numerous literary works and academic studies regarding women’s voices, being silenced, and the inherent differences between the way the sexes communicate, the feminist movement—brave, bold and daring at its best—has never been able to make substantive changes in the ways we communicate.

The problem? Our very language itself, as well as the nature of the culture we’re raised in. You’ll find that you can’t have one without the other; I’ll explain.

We are all raised in a culture that uses certain, very specific, metaphors to describe life experiences. Our culture privileges language use that is “straight as an arrow.” We like to “get right to the point.” If you live in a culture that doesn’t do this, it’s likely you’re not from the West, and, most likely, you’re not an American. In America, in particular, everyone, male or female, is raised with the same set of expectations. It’s a linear culture. We expect our answers to be simple and straightforward.

In fact, I’m having trouble writing this sentence without using the standard metaphors we usually rely on. How do I find another way to say “straightforward”? I’ll have to use my thesaurus. How do I find another way to say “stay on track”?

The key to our language use are the ways in which language choices are determined by cultural values. Although we aren’t usually consciously aware of the underlying “why” of why we say the things we do, those sayings are, not-so-subtly, in my experience, shaping not only how we speak, but also how we think. We are never set free from the expectations of our culture as long as we use language unconsciously.

How does this affect you as an individual, especially one who is, perhaps, confused about what you want from life? If I had you sitting in front of me, would you beg me to “get to the point?” Even feminists say these things, which leads me directly to my point (for which my linear readers will, no doubt, thank me). Even those of us who promote humanist and feminist agendas are not free of our language use, because we’re never free of our culture and all its expectations.

Here’s the core of the problem: We might speak using the metaphor of linearity, but it isn’t how we think. We’re curvature-type people, we humans. We tell stories that go around and around. When asked to explain something that just happened to us, we might not start “from the beginning”. We’re maddening like that. It isn’t just women, either; men do it too. The human brain doesn’t work precisely the way our slapdash “time is money” culture would like.

And so those who need more time, more words, more creativity, are silenced in the face of the tapping foot of the impatient, narrow-minded linear metaphor. Another factor that contributes specifically to the silencing of women, however, is more pernicious and less easily spotted, and it feeds into the linear metaphor neatly. It is the culture we exist within, the culture of scientism, which is inherently distancing, mechanistic, and dehumanizing.

In case you don’t know what I mean, consider that until fairly recently, it was considered bad manners to speak in the first-person pronoun. One used the less personal pronoun, “one,” to describe one’s wants or needs. It was (and still is) considered grammatically correct, and although that’s useful when grammatically-correct writing or speaking is called for, it symbolizes the problem, which has to do with impersonalization, the distance between “I” and “one”.

Further, if you listen carefully enough, you’ll begin to notice that we not only live within a culture that privileges linearity; we also rely on a vocabulary of numbers, weights, measurement, and mathematics—the vocabulary of science. Although this part of my argument is too large to adequately address in one short piece, I will suggest that if you eliminate the vocabulary of science, as well as linear metaphors, from our language, there wouldn’t be much left to say.

Try it for a day; see if you can condense (a word borrowed from scientific experiments) your conversations into that which does not rely on science or linearity. It will prove (a science word!) to be a challenge. This is especially true in the land of academia, which is imbricated (my favorite academic word, which simply means “bricked in,” as in, “the woman was bricked into the wall, buried alive”) in scientific terminology, over-relying as academia does on proofs, hypotheses, and problems to solve.

So, if we are raised in a culture that uses two particular methods to express itself—one, the metaphor of linearity, and the other the vocabulary of science—then what should those who are caught in between do when they are voiceless in response to this impersonalized, mechanistic, linear methodology of thought? Feeling like you’ve been absorbed by the Borg yet? You should.

When a woman encounters a direct question about her inner landscape, therefore, everything she’s been taught to think is at war with the one metaphor that makes sense, the metaphor of organicism.

The metaphor of organicism includes the body, and does not exclusively privilege the mind. You will notice a few things about scientific vocabulary and the metaphor of linearity: they both came to social prominence during the rise of scientism, otherwise known as the Enlightenment, the era of Reason.

It was called the ‘enlightenment’ because its role was to cast light into the darkness that came before it, including the darkness of superstition, paganism, and what was perceived as the ‘ignorance’ of faith. This included the lack of knowledge about how the body, but most particularly the mind, worked.

Many important ideas were swept away during the Enlightenment, however. When society emerged from what became known as ‘the dark ages,’ we were no longer allowed to think like Plato (after the rise of Christianity, considered a pagan), who gave us the metaphor of organicism (an idea later appropriated by the Romantics, which only served to deepen the divide between that which is produced by nature, from all that is ‘man-made’).

The Romantics rediscovered Plato, the body, and emotion. Without them, I doubt we’d be having this discussion.

Instead, Western society started thinking like Bacon, Locke, and Descartes, all of whom much preferred applying reason and, most importantly for my argument, logic, to life questions. In swept the rise of linearity and scientism.

Unfortunately for those of us who are not inherently scientific and linear, however, when we lost the organic metaphor, we also lost all that went with it, including metaphors relying on our bodies as a way of explaining reality. If you don’t buy into the metaphor of linearity (you don’t perceive the value in it) and you’re not inherently interested in the scientific way of approaching reality, where do you stand, especially if, now that logic is the dominant trope, we have no bodies, only brains?

I used to teach English composition at a research and development university. Frequently, my students were pursuing a science-related degree. Nothing about the training they’d received, or their life experiences, for that matter, prepared them for my style of teaching. I had one memorable day in particular when a student asked me why they had to use the personal pronoun “I” in their papers. Her question led to a 15-minute diatribe from me about the depersonalization in society brought about by the sciences and its perpetuation of emotional distancing.

For me, the reason scientism is such a problem is because it tells us that it’s okay, even desirable, not to use the personal pronoun—this means we forget to think in terms of our inner “I”. The prevalence of the metaphor of linearity reinforces the idea that we must ‘keep to the path,’ ‘keep to the straight and narrow,’ that we must not diverge from ‘the norm.’

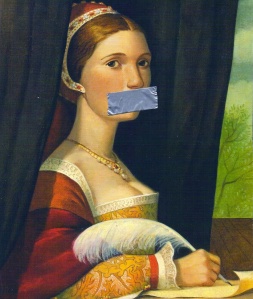

Women’s speech has always been a concern. This tarot card draws on a folk tale from The Blue Fairy Book (1889). Tarot cards are an example of non-linear uses of metaphor, as are folk tales and “old wive’s tales.”

Who, under the influence of a society adhering, unconsciously, to these rigid, linear, rules, would allow themselves to meander a little, to stray from the path, watch daisies grow, or imagine himself in another, more colorful reality? To, heaven forfend, daydream aimlessly?

Finally, consider this: I think we’d agree that most, if not all, women in what we’ve come to think of as third-world countries lack what we’d call a ‘voice.’ We have no idea how an individual Pashtun woman, for example, thinks or feels about her life. We rely on educated men and women to tell these otherwise silenced women’s stories, just as the tribal woman herself relies on those from the West to tell her story, until or if she becomes educated, and self-confident enough, to tell her own story.

One thing is certain: those in the West will tell her story their/our way, using the dominant vocabulary and metaphors we all rely on to convey meaning.

And yet, these isolated, tribal women, nameless and faceless to most of us, are no more or less silenced than a woman in the West, if that Western woman, with every privilege, every social advantage, feels voiceless; that she is, effectively, silenced, by a culture that has given her a vocabulary she doesn’t identify with, and a set of metaphors she doesn’t believe in. Under those circumstances, you’re not using the language; the language is using you.

Feminism located one source of the problem for women: that we try to express ourselves while using the language of ‘the patriarchy.’ What feminism couldn’t accomplish, however, was to undo the prevailing beliefs and values that created that dominant language and vocabulary in the first place. Using a language unconsciously, we are stuck within it. Knowing that the metaphors and vocabulary binds you helps you break free of them, as well as some of their more pernicious expectations. What do you replace them with? That’s the challenge we all face, in my opinion: we must come up with a more inclusive language, one that more accurately reflects human reality—mind and body.

Ask yourself what’s preventing you from being heard, being seen, being known. The answers might surprise you; but what shouldn’t surprise you is that, if you’re a woman, you’ve been taught to think in such a way that prevents access to this complex inner world, for it’s a world that is recursive, not linear, and not necessarily bound by logic or language, either. Many of our deepest truths occur without ever attaching themselves to words. Much of what we know at the unconscious level are things we learned before we ever learned language. If you insist that it’s easy to give voice to places in your mind that are pre-verbal, therefore, you’re fighting an uphill battle.

The truth is, we’re not ‘straight as an arrow.’ In many ways, we’re curved. Only one one of those ways is physical.

Related articles

- Mormon Women Declare “Wear Pants to Church Day” December 16 (religiondispatches.org)

- Fuck You, Men’s Rights Activists (jezebel.com)

- Good News, You Guys Everyone! English Is Becoming More Inclusive (theatlantic.com)

You must be logged in to post a comment.